This is how we've put a game inside a game (Yes, it's iframes)

This is more of an article than a dev log and it's mostly intended for people unfamiliar with web development. We'll talk about how we put other people's games inside a phone in our game, including some technical details and some web basics

TL;DR:

- To display other people's games on top of our game, we've used <iframe>, because both our game and all others are built for web, i.e., HTML documents that run in a browser.

- To insert and actually control that <iframe>, we've injected Vue.js app in godot's html-template and set-up interop.

- Godot-Javascript-Interop exists, but a nice and clean workflow is still a bit of a challenge.

- It all worked because itch's CSP allows it.

Contents

What is iframe?

If you ever poked around in your browser with "inspect element" to, for example, grab image urls, doctor some text, and what-not, you've probably noticed that pages are build with things like <p>, <img> etc. - those are HTML elements, serving different functions.

For example, <p> is a paragraph - displays text, <img> shows an image when provided with url, <a> is a link and so on.

Pretty much, each "site" you visit is HTML Document - just a collection of those elements, styled with CSS and made interactive with JavaScript. It's just that over the years, a lot of api's and other things were added to browsers that allowed building app-like experience, but at the core - it's still just HTML documents.

So, iframe (or "inline frame") is an HTML element that allows you to embed whole another HTML document within the

current

one. Hence, with some important caveats in mind (which will be discussed later), you can think of an iframe as a browser tab

inside a

browser tab

In fact, if you've been on itch.io for a while, this is how browser games are usually embedded into the page.

Anyway, an important bit here is that since a browser game on itch is just an HTML documents, then pretty much whatever modern browser can do - you can put in your game, regardless of an engine you're using!

Let's just put an iframe on top of another game right now!

First, since you're already reading this devlog, let's go to our game

Since embed does not exist, until you press "run game" - press it.

Now, right-click anywhere on the page and select "Inspect"

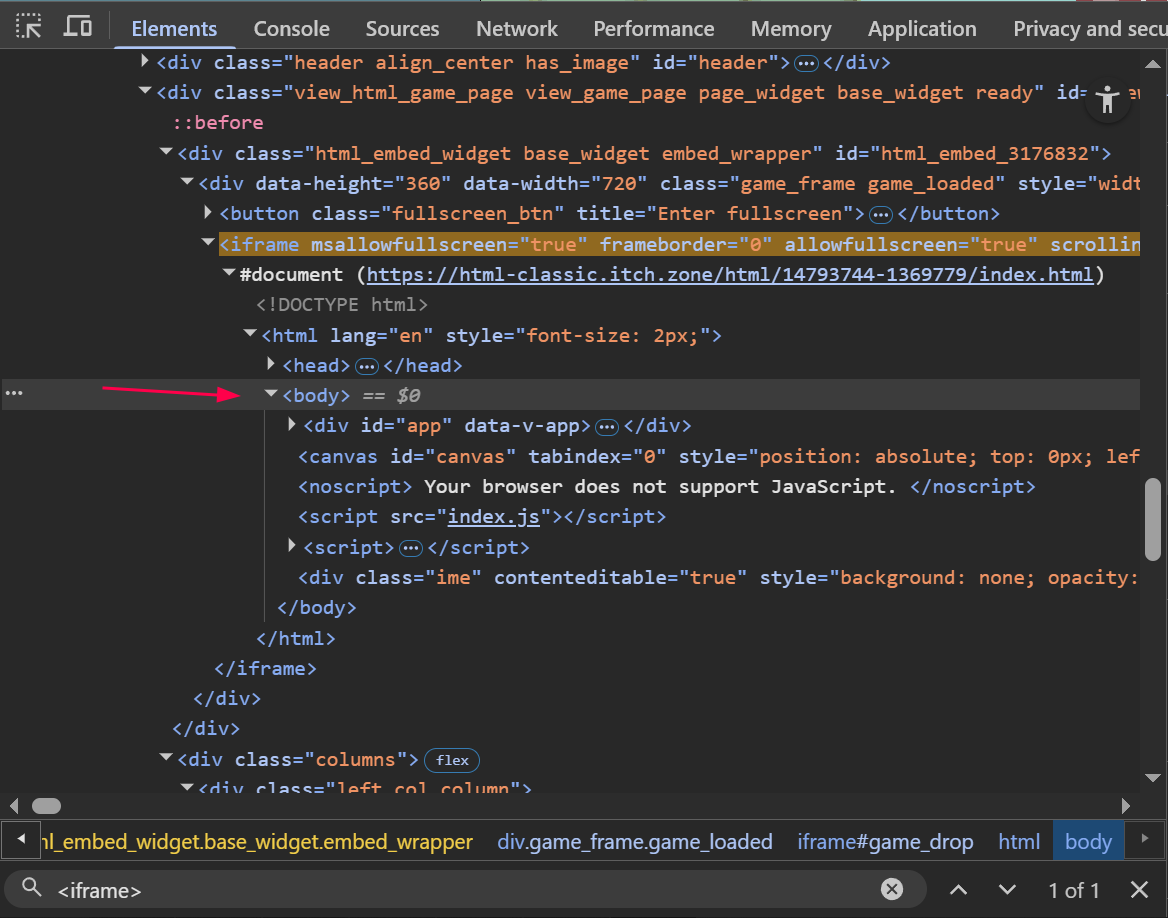

In the inspector, find the <iframe> element (you can use ctrl+f to search for it)

Once you find it, keep clicking on arrow next to it until you reach <body> element:

We've found a suitable place, now let's add some code!

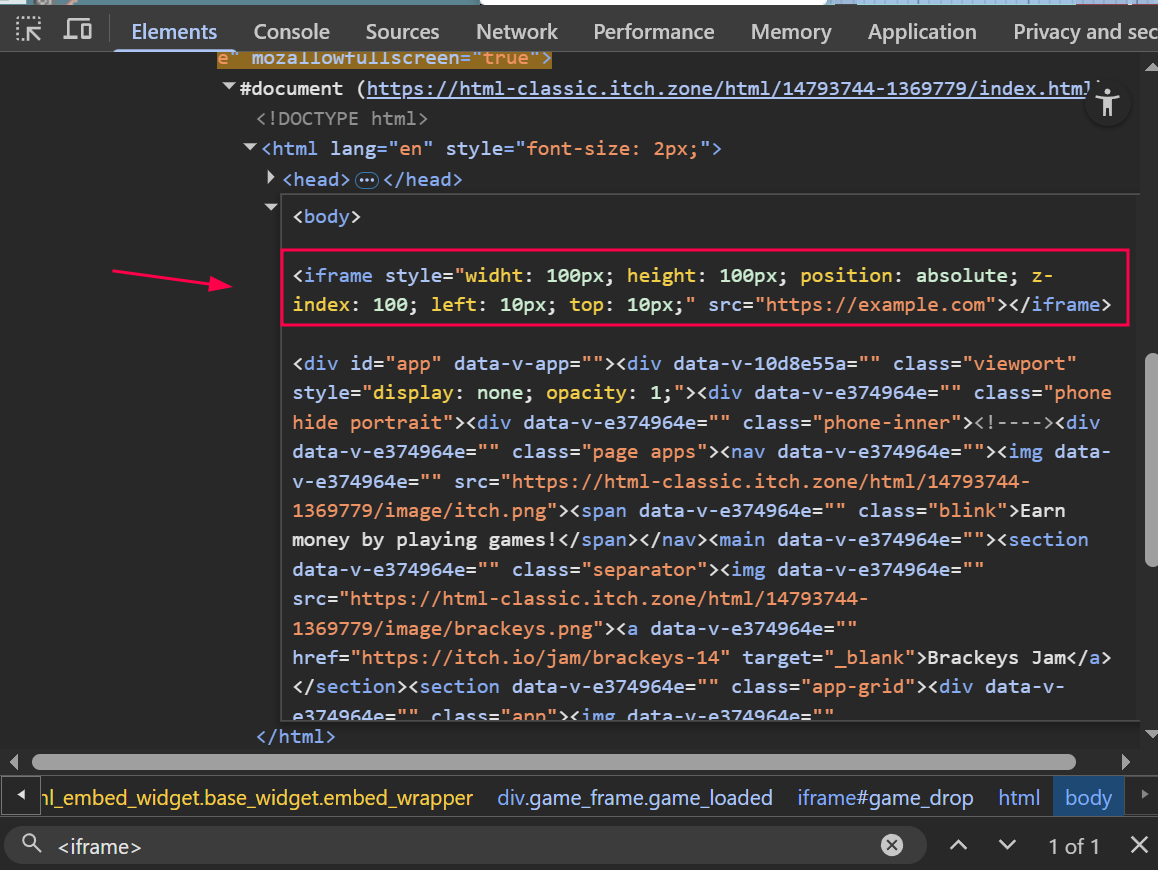

Copy this:

<iframe style="width: 600px; height: 340px; position: absolute; z-index: 100; left: 10px; top: 10px;"

src="https://example.com">

</iframe>

Right click on <body>, select "Edit as HTML"

Paste the code between <body> and first <div>:

Once done, click anywhere outside the code block or press ctrl+enter

After an example.com finishes loading - you will see a white box with a text "Example Domain" on top of a game.

And that's it! Essentially, this is how we display other games inside our game!

You can even try it with your web game, just change src attribute to something like https://html-classic.itch.zone/html/14793744-1369779/index.html

Limitations and Security

At this point, you might have a few very legit questions, like "Does it mean I can put any site on top of my own?" or "What stops hackers from, say, registering a domain like "pwnpal dot com," putting legit PayPal on top of it and stealing money by tricking people to go there?"

Well, there was a time when it was a legitimate threat, and this kind of attack even has a name: Clickjacking. The name comes from the idea of "hijacking" a user's clicks.

Malicious actors would layer an invisible iframe with a legitimate site (like a bank or social media) over a seemingly harmless page. They could then trick you into clicking buttons on the invisible page, making you perform actions you never intended, like transferring money or changing your password/email.

Thankfully, the days of this being a widespread, unchecked threat are behind us. Modern browsers have robust security mechanisms in place to prevent it.

In fact, if you've tried to load a game page instead of an embed:

<iframe style="width: 600px; height: 340px; position: absolute; z-index: 100; left: 10px; top: 10px;"

src="https://pontax.itch.io/snail-racing">

</iframe>

You would get an error mentioning Content Security Policy, so what's the deal here?

It's All About Trust and Headers

When your browser asks a server for a webpage, the server sends back the HTML content, but it also sends a collection of HTTP headers. You can think of these headers as metadata or instructions for the browser. They can tell the browser how to cache the page, what type of content it is, and, most importantly for our case, how it should be handled from a security perspective.

To prevent clickjacking, a server can include a header that tells the browser, "Do not allow this page to be rendered inside an iframe on another website." There are two main headers used for this purpose:

`X-Frame-Options`This is the older, but still widely supported, header. A server can set its value to:DENY: Completely prevents any site from loading the page in an iframe.SAMEORIGIN:Allows the page to be loaded in an iframe, but only by pages from the exact same website (origin).

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestorsThis is a newer, more powerful directive that is part of the broader Content Security Policy (CSP) standard. It gives website owners fine-grained control over who can embed their pages.

For example, a server can set a policy like:Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'self' https://trusted-partner.com;

This tells the browser that the page can only be embedded on pages from the same origin (`'self'`) or on pages from `https://trusted-partner.com`.

So, in short, itch, PayPal and many other sites set those headers to tell the client browser that "this content should not be embedded in iframes on other sites." This is why, when you try to load them in an iframe, a proper browser blocks it and shows an error instead.

However, some sites, like example.com, do not set these restrictive headers, which is why we can load them in an iframe without any issues. The same is true for html-classic.itch.zone, which actually hosts and serves web games - and this is exactly why we were able to put other people's games on top of our game

In short, we were able to put games there because itch either allows it, or it's just an oversight.

Some other caveats

Besides X-Frame-Options and CSP, here are a few other things to keep in mind about iframes:

- Can't mute sound coming from an iframe (unless they are on same origin, and you can find all the audio/video elements and mute them)

- Can't interact with content inside an iframe if it's from a different origin (due to the same-origin policy). This means you can't read or modify the content, styles, or scripts of the embedded page.

- Limited inception levels :) - could not find documented hard limits, but nesting the same site (playing snail game inside SnailRacing inside SnailRacing) is not possible - browsers don't allow it. Though, you can play other games inside SnailRacing that is inside SnailRacing.

-

Styling and Visual Integration

An iframe acts as a complete "black box" when it comes to styling. Your parent page's CSS stylesheets have absolutely no effect on the content inside the iframe. You can put a border around the iframe element itself, but you cannot reach inside to change the embedded page's background, fonts, or colors.

In our context: This means the visual experience of the embedded games is entirely up to their original developers. You can't enforce a consistent look and feel to match your phone UI from the outside. If a game has a light theme and your page has a dark theme, you're stuck with that visual clash.

-

Sizing and Responsiveness

Making iframes work seamlessly in responsive layouts is a classic web development challenge. An iframe does not automatically resize to fit its content; you must give it a fixed width and height. If the content inside the iframe is larger than these dimensions, the browser will add scrollbars, which can break the user experience. The parent page has no easy way of knowing the actual size of the content within a cross-origin iframe to adjust its height dynamically.

In our context: This is very relevant for phone UI. If a game is designed for a specific aspect ratio that doesn't perfectly match the "screen" of an iframe, the user will either see ugly scrollbars or the game will be cropped.

Godot and Web Integration

Now that we understand at least something about iframes and web in general, let's talk about how we can integrate this concept into a Godot web game.

Entry point

When Godot exports a game to HTML5, it generates an index.html file that serves as the game's entry

point. This file contains the canvas for rendering and the JavaScript code to initialize the engine (and some other

things that are not important right now)

Therefore, to inject our own elements and scripts, we need to modify this index.html file.

Custom HTML

Reasonable way to modify index.html godot is producing is to change the HTML template and set it in

export parameters, as

explained here

Basically, the same way we've added an iframe directly in browser, we can just insert there - and it will be rendered each export, no big deal

However, in SnailRacing we needed to do a few more things, like making iframe follow the phone screen, list games, load games, etc. - in other words, interact with godot game, which brings to the next topic:

Godot-js-interop

Basics of interaction between godot's gdscript and Javascript running in browser are covered here.

You can try a few examples from, but it mainly boils down to this:

Calling Javascript from gdscript

if you add the following to your template:

<script>

window.testCallJsFromGodot = function () {

console.log('testFunction was called from godot with arguments', arguments);

};

</script>

And then, in your gdscript you do:

if not OS.has_feature('web'): # prevent errors when running outside web

return

var window = JavaScriptBridge.get_interface("window") # get window object

window.call("testCallJsFromGodot", "arg1", 42) # actually call testFunction

You should see a message in your browser console, listing all passed arguments

Calling gdscript from Javascript

It's a bit more complicated, but here's what you do in godot:

# attach this script to any node in your scene

extends Node

# a reference to bind javascript and godot functions together

var _callback_ref: JavaScriptObject = JavaScriptBridge.create_callback(_js_callback_implementation)

func _ready():

if not OS.has_feature('web'): # prevent errors when running outside web

return

window = JavaScriptBridge.get_interface("window") # get window object

window.testCallGodotFromJs = _callback_ref # bind js function to godot callback

func _js_callback_implementation(args):

print("Arguments received from JS: ", args)

so then, when the game finishes loading, you can execute this in the browser console:

window.testCallGodotFromJs('Hello from Vue!', "arg1", 42);

And you should see a message in godot listing all passed arguments

Footnotes:

What's the deal with "window"?

When you run JavaScript in a browser, you have access to window interface, which represents, you've guessed it, a window (more exactly, current tab).

Two important bits here are:

windowis accessible everywhere in the code- Since JavaScript is dynamic, you can add properties to

windowon the fly, and they will be accessible globally

Generally, it is considered a bad practice to add things to a window on a whim, but sometimes you gotta do what you gotta do)

Remember emphasis on "finishes loading"?

This is related to how HTML works. Basically, when you load a document, a browser goes line by line (unless "defer"-ish stuff is specified), evaluates and executes each script one by one, which means that until godot fully loads and adds our testCallGodotFromJs to a window - you can't call it.

Anyway, here are a few problems I've found with this godot-js-interop during jam:

Intellisense/autocomplete

When defining a JavaScript function to be called inside gdscript, I haven't found a way to inform my JavaScript project of this function's existence and signature. The same is true when declaring callbacks in gdscript. Basically, you won't have autocomplete/warnings if you mess up the function name/arguments and won't know something is wrong until you run it.

We've definitely not lost any time on those typos during jam crunch, wink-wink)No Promises?

Right now, there seems to be a way to wait for promises on a godot's side, when calling async JavaScript function

On top of that, while working with JavaScript in this day and age, you probably want types, package manager, bundler, and hot reload - all the good stuff, but it's a bit problematic.

During the jam, we kinda-sorta "achieved" modern web workflow by making a vite-vue project, here's how it worked:

- We had a separate folder with a vite project, with its own package.json, node_modules, etc

- During each iteration on godot's side, we've run build for web project, which produced godot's index.html and js bundle

- On a vite's side, we've made a script, that would patch(oh god) resulting index.html to vite's project code.

- After patching, it was possible to work on a vite project with hot reload, types, etc. - and see changes in the browser immediately

- After vite iteration was complete, we've run vite's build script to generate a static build, so it could be put alongside godot's bundle

- The finishing step for uploading the resulting mess was a call to buttler cli

At this point, you'd be right to ask, "Hey, you just talked about a nice and clean way of adding custom HTML, why are you patching all of a sudden?"

Right, here we have a bit of a chicken-egg problem

If you look at godot's HTML template, you'll see things like $GODOT_URL, $GODOT_CONFIG -

those are tokens, that are replaced with proper data during godot's build, which means that until we actually build

godot project - we don't know them

So, if we just base our vite project on godot's HTML template, to have a complete game running using vite's dev server (which provides hot reload and stuff), we would need to build godot's anyway AND somehow get data for those tokens

As of right now, it's not clear how to make it nice and clean

"But I don't want your bundlers and stuff, jeez, what do I do?"

Fair enough, if you don't want to deal with all that mess and your scope is pretty small, you can just add your scripts and styles directly to godot's HTML template, use plain JavaScript, and build your game normally.

Final words

As you can see, no black magick was involved. It's all just basic web shenanigans

Though, we think it never hurts to learn a bit in depth

Let us know if you're interested in the topic and, especially, if there are mistakes in this article

Also, thanks for playing!

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

Cool read!